| |

Chris Anderson is a hard worker. If she talks about a work, you find she means eighty paintings, or a hundred paintings before she's explored an idea. Accolades and prizes have come her way, but she doesn't seem to hold them very tightly. Not that she isn't grateful, it's just that her focus is on the great tide of work ahead. The Fulbright Commission awarded Ms. Anderson a lecture/research grant and a renewal as an Honorary Fulbright Senior Scholar. That got her to Germany, but getting her home again was another matter. Returning to America, neither NEA nor NYFA Fellowship grants, Yaddo nor MacDowell residencies, guest faculty nor visiting artist positions spared her the infamous search for a studio in crowded New York City. It had taken two years.

I was able to interview Chris just as she turned the key in the lock to her new space at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts Studio Center in New York's historical Garment District. We went in together for an initial survey. In inevitable art–radiates-from-life fashion, this artist's life-theme, like Odysseus', is the search for home. No worthy art isn't based on our lives. Therefore a homecoming brought me into her new studio—the heart, the very kitchen, of an artist's home. Here, however, is a studio with no paint, no easel, no brushes, no work. Baby-skin new. What does on artist next pursue when not only the canvas but also the studio is blank? How does one go about making a home, especially if it is the very subject of one's work? As we sat on the floor of this naked studio, late afternoon light and city street noise pouring in, Chris spoke on that topic:

GB: Can an artist really trace how one arrives at a particular theme—in your case, the conception of home? Is it possible to trace out consciously how one arrived?

CA: Yes, but let me mention one highlight along the journey. One summer I moved to Dallas, Oregon, to be with my grandmother. This was the woman who had taken me to my first museum, supplied me with art supplies throughout my childhood and delighted me with endless stories of Anderson pioneers on the American frontier. She was then 100 years old, partially paralyzed, blind and deaf. I found hefty head phones through which she could hear and dug up Victorian music from her youth. I fed her, stroked her, sang to her, read to her, brought her things to touch and feel, pushed her wheelchair through the park and simply loved her. Over the summer she came alive.

While she would rest, I would go out and cruise the streets of suburban homes, tracts of seeming sameness. Oh, I was a total snob, critical and elitist. I came across a small ranch house bedecked by flowers and surrounded by gardens. I was humbled when I realized that someone with little means was creating a castle and I'd failed to see it. I'd missed the deeper, transforming expression. It was at that point that I lost the ironic edge to my work. One of my paintings from this period was based on Masaccio's Expulsion. The archangel drives Adam and Eve out of the garden and into a suburban West Texas street. I still work with dislocating or relocating points of place in points of time, and I remain critical of most postwar suburban architecture (or the lack of it), but I've lost my elitist virginity. I see the lives within, life from the other side of the wall. I stepped through the door, into the home, and its been different for me ever since.

To be at home in the universe—what does it mean? "To dwell as a mortal," as unpopular Heidegger would say? And to feel one is not fully at home in this place? I've tried to deal with this in three series of works: My Home Is My Castle, Family Stories and At Home in the Landscape: Earth & Memory within a larger body of work called Historical Dislocations. In the past I'd been painting the house from the outside. Now I paint it from the inside, how it exists not only physically, but also spiritually and emotionally.

GB: How did "home" evolve into "castle"?

CA: The initial reason I went to Germany was to investigate the relationship of the contemporary home to the historical castle—and Germany has some of the best! It was inevitable, that after working with the concept of home, I would repeatedly run up against the old proverb "My home is my castle." This simple saying became the starting point for my Fulbright work. I began seeing a connection between the postwar home and the ancient castle as fortress, private domain, symbol of power, sanctuary, and romantic ideal.

This historical castle and the modern suburban home do share common raison d'etre: the sequestration of the dweller from the problems of an external environment where only the powerful could achieve privacy. Centuries later the suburban dweller strives for the same ideal: the privatization of life. Through the ubiquitous medium of the Internet (not to mention the television)—a type of technological "periscope" or "castle tower" to the outside—the suburbanite becomes, in a sense, omnipresent. "In the world, but not of the world," he is spatially, but not culturally, separated. Within his borders, he has attained privacy and power. His home has become his castle.

GB: The site-specific connections you describe remind me of Flannery O'Connor's statement in Mystery and Manners: the artist penetrates the concrete world in order to find at its depths the image of its source, the image of ultimate reality. What O'Connor concludes from this is astonishing, "when the physical fact is separated from the spiritual reality, the dissolution of belief is eventually inevitable." You recently had a tragic encounter with this experience. Can you tell me how you came to embed ashes from the World Trade Center disaster into a piece?

CA: Yes, well, the concrete world. I really did work with concrete—concrete dust and ashes. I was there. I felt compelled to take some of this dust over everything, this omnipresent gray ash. I didn't take much, just a handful. Any more would have been obscene. I found a plastic bag—a little plastic bag to put some in—and I carried the ashes in my purse far the longest time. In Italy several months before, I had worked with earth, local earth mixed with raw pigment and pastel. I was making these pieces about the earth—Earth & Memory, Terra e Memoria—local landscapes of Umbria and surrounds. I'd been carving the landscapes into the paper with tools that cut, embossed, gouged and scored. I call it "excavating the surface" in the manner of archeologists excavating a site or farmers tilling the same earth for a thousand years. The Italian landscape is so embroidered with human etchings, with the marks of humanity, and tattooed with design elements: line, rhythm, farm, shape, color, texture. Countless years of tilling, sowing, planting and harvesting record the histories of lives at home is the landscape. I attempted to reflect this in the artmaking process, in the way I made the work. I excavated the paper. I tilled it. Then, I plowed the pigments and the earth into the virtual wounds of the paper.

When I returned to Orvieto for a show in October, I created a final piece with the ashes I had so long carried. On the eve of the opening, I was bent over a low table like Picasso's old woman over her iron. The piece seemed to make itself. Two great, bright shapes rose in a conflagration behind the dark silhouette of Orvieto. I sowed the ashes into the three negative spaces between the towers. The opening of the small package and the sprinkling of the ashes felt like some sort of one-time ritual, an embodying of something deeper. I realized then I was handling not only concrete and steel and plastic, but also the very flesh and bone and blood of those who died September 11. I began weeping and I could not stop. My tears fell onto the paper, into the ashes, into the mix. Water and fire. I think the experience for me was a kind of grieving—not only the greater family lost September 11, but also recent losses in my own small immediate family.

GB: Chris, after going around with you the last few days I have a strong sense that, like William Blake, you're more willing than most to unclothe your imagination in the harsh light of day.

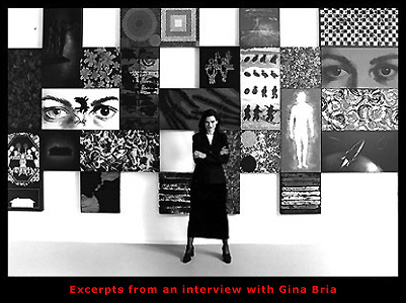

CA: Imagination! I've given lectures on art and aesthetics, on the complex relationship of faith and art, on the artmaking process, and I'm no closer to understanding this phenomenon than when I was a child enhancing the walls of my bedroom with crayons! I think of the story of the woman seeing her daughter making a drawing. "What are you drawing, honey?" Her daughter replies, "God." "But darling," the mother says, "Don't you know that no one knows what God looks like?" She responds, "They will when I get done." That's the balance between imagination and reflection. I believe the Genesis mandate "be fruitful and multiply" may be translated as cultivating and nurturing the earth "to bring forth its glories." I see imagination as the best form of play, the kind that draws tears and sweat and joy. I especially saw it at work in my East Berlin studio when I preassembled the most complex of the wall installations of the Family Stories exhibitions.

GB: So you really are talking about play here-imagination manifest.

CA: The best, deepest manner of play. For days I "tweaked" the nearly forty panels in a great, perforated modernist grid spread out on the studio floor. I moved the units about like children's blocks, like moves on a gigantic board game. Arranging the paintings on a huge, room-size field made the process seem like play. I slept in the studio, close to the paintings. I literally built a home out of canvases. Each painting became a "Baustein" in the wall of the house. The paintings—inspired by a family archive of items of memorabilia spanning three family generations (grandmother included)—each told a short story, a moment in the life of a family. I'd orchestrate the visual "voices" so they'd sing together. It was an exciting work experience, an immersion in hard work and pleasure. I felt part of the genetic code linking my family with every family, that I was carrying the information for them in some microcosmic way.

GB: Do you know Joseph Conrad's adage that the aim of the artist is to render the highest possible justice to the visible universe?

CA: I look at art, and it looks back at me. In The Inward Vision, Paul Klee wrote, "art does not reproduce the visible; rather it makes visible." I, and generations of colleagues past and present, have attempted to make visible the invisible…

Gina Bria, an anthropologist, is a Berlin fellow with the Institute on Family Development. Her book The Art of Family (Doubleday Bantam Dell), was published in 1998. She lives in New York City with her husband and three children.

BACK TO TOP

|